There seems to be nothing in your cart.

Didn't find what you were looking for? Contact our consultant.

To save your shopping cart until your next visit, create an account or register .

Browse our Hits sales

There seems to be nothing in your cart.

Didn't find what you were looking for? Contact our consultant.

To save your shopping cart until your next visit, create an account or register .

Browse our Hits sales

*Attention! The author of this article does not encourage the use of psilocybin mushrooms and reminds us of the importance of a responsible attitude to the laws. All information provided is for informational purposes only.

Contents

Magic mushrooms have been known to mankind since its very first days on earth. Having appeared at the dawn of history, they accompany man right up to the present time, invisibly but palpably present in many areas of our lives. As in any cosmic-scale scenario, the topic of mushrooms is initially shrouded in a veil of mystery and mysticism. Throughout history, magical and medicinal properties have been attributed to mushrooms, and some even linked the nature of magic mushrooms to God himself! Consider the hypothesis described by Terence McKenna about the connection between magic mushrooms and the evolution of the brain of the first people - “Stoned Ape Theory.”

What about the well-known biblical scenarios of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden (with new details), where the reason Adam realized himself was not an apple, but a magic mushroom? The Aztecs called these mushrooms “teonanacatl” - “body of god”, but only the chosen and initiated used it. Rituals using hallucinogenic mushrooms have been preserved among Central American tribes until the present day.

There are about thirty thousand registered species of fungi in the world that are capable of producing fruiting bodies (mushrooms). About one hundred species or varieties are known to contain psilocybin or related compounds such as psilocin, baeocystin and norbaeocystin. Most of these are found in the genera Psilocybe and Panaeolus, and some are found in other genera, such as Inocybe, Conocybe, Gymnopilus and others. Of course, not all mushrooms in these genera or families contain psilocybin, and even those that can produce it often only produce it in trace amounts. Since different types of psilocybin mushrooms contain different levels of alkaloids, the required dosage therefore varies. This must be taken into account when meeting new species.

The 20th century of our history is gradually dispelling the fog of mysticism around the topic of psychedelic mushrooms. Psilocybin mushrooms were studied from the 1950s to the 1970s by several prominent scientists, including Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert of Harvard University. They talked about the mind-expanding properties of mushrooms, which are somewhat similar to synthetic drugs such as LSD. However, the widespread use of these mushrooms for recreational purposes has prompted state and federal governments to strictly control them in many places.

The brilliant minds of the past, scientists, doctors, philosophers, and artists are joining the research. The topic of psychedelics is beginning to take on more and more precise outlines. There are discoveries and breakthroughs in the field of chemistry, biology, neurology, psychology, etc. Albert Hoffman's discovery of the psychoactive properties of LSD in the middle of the last century marks the beginning of formal research and use of psychedelics. A large number of open research, conferences, and investments are being conducted. The isolation of pure psilocybin by Hoffman in 1958 dates back to this period. Further in history, there is an unprecedented increase in the popularity of this topic, just like the wave of the hippie movement, the echoes of which are quite clearly heard today in different parts of the world. It is difficult even to briefly cover all the current trends in the development of this area; it is only appropriate to emphasize the globality and reality of the scale.

In the 21st century, psilocybin mushrooms have been tested as a treatment for chronic mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, addiction, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the United States, the Department of Veterans Affairs is testing psilocybin and psilocin to reduce mental health problems among veterans and suicide rates. Although scientists are still trying to understand how these mushrooms alter brain function, some results suggest that their active components may have the ability to break down old neural connections and create new ones, potentially reducing negative or obsessive thinking and allowing patients to develop more positive behavior and worldviews. overall.

Psilocybe cubensis is the most widely cultivated species of psychoactive mushroom for historical and biological reasons. Worldwide, it is one of the most common psilocybin-containing species found in the wild, and therefore among the most commonly consumed and best known species. It is also one of the easiest to cultivate as it bears fruit in a wide range of substrates and environmental conditions. Although in the wild it grows exclusively on manure, when cultivated it will bear fruit on almost any type of substrate sufficiently rich in carbon and nitrogen: straw from cereals, on grain, on grass, even on wood chips, paper or cardboard if supplemented with some either a form of protein or sugars.

Most species of mushrooms are quite picky in their requirements for substrate and conditions for fruiting, but not Psilocybe cubensis. This fact, combined with its fairly high amount of psychoactive compounds, makes it one of the best types of mushrooms for the beginning cultivator. We recommend starting with Psilocybe cubensis because it is the easiest to grow and is the type of mushroom that contains psilocybin that people are most familiar with. Its fast-growing, rhizomorphic mycelium, abundant primordia, large fruiting bodies and abundant spore production, all of these factors make it the quintessential magic mushroom that is easy to grow at home. Only after you have gained experience growing a given mushroom and become familiar with its life cycle will you be ready to work with species that behave more “capriciously.”

Psilocybe cubensis is a tropical and subtropical mushroom that grows abundantly on the manure of cattle, horses and elephants, or on soils containing their manure. It can be found almost anywhere in the world with a humid and warm climate, including Southeast Asia and Australia, India, Mexico, Central America, northern South America and the Caribbean. It is one of the largest species containing psilocybin, with a cap measuring 5 to 15 centimeters in diameter and a thick stalk up to 20 centimeters long. When grown on grain or rice it is usually modest in size, but when grown on manure or compost it can produce huge, even colossal-sized mushrooms. The spore print is often "bold" and consists of purple-brown spores.

When the Psilocybe cubensis mushroom is “injured,” “bruises” or blue spots often remain on its fruiting body. Although such a trauma response that produces blue spots often indicates the presence of psilocybin in the mushroom, such blue discoloration in itself cannot be considered definitive proof, since there are other types of mushrooms that lack psilocybin but produce exactly the same reaction with " turning blue." Additionally, a lack of response to blue spots does not necessarily rule out the presence of psilocybin-like alkaloids in the mushroom. The blueing reaction occurs when psilocin (or another chemical agent) oxidizes into an as yet unidentified dark blue chemical compound. Mushrooms containing low levels of psilocin but significant levels of psilocybin will not turn "blue" despite their apparent psychoactivity.

Psilocybe cubensis is considered moderately potent compared to other psychoactive mushroom species. It may contain up to 1.2% (dry weight) of psilocybin, psilocin and baeocystin, with an average of somewhere around 0.5% or 0.5 mg/gram.

While such averages are useful benchmarks for comparing the potency of one species to another, it is important to keep in mind that potency can vary widely among mushrooms of the same strain. Certain strains, or the same strain grown under different conditions or on different substrates, may exhibit dramatic differences in activity. Even the same strain can vary in its psychedelic properties from one harvest wave to the next, with the second and third harvest waves usually being the most potent.

There are species of Psilocybe that love wood as a substrate. Although Psilocybe cubensis is very easy to grow, there is one type of indoor growing that it is not well suited to: outdoors. In nature, of course, it grows outdoors, and it can certainly be grown in a garden or park, but there is no particular advantage to this. The two main benefits of creating a “mushroom bed” in your garden is that it can be either a perennial crop or a “secret” garden. You create a similar “mushroom bed” in a hard-to-reach place, remember this until it begins to bear fruit, then collect mushrooms, and then “forget” about this bed again until the fruiting process repeats next year.

Once a secret mushroom bed has been created, the bed should be more or less a self-sustaining system and completely unnoticeable except when it is bearing fruit. Psilocybe cubensis is not suitable for growing in an outdoor mushroom bed for a number of reasons. First of all, it bears fruit quickly and continuously until its substrate is depleted of nutrients and its mycelium is unable to live long enough to be considered perennial. Secondly, this fungus grows and reproduces on a wide variety of substrates, but a number of other undesirable macroorganisms and microorganisms can also live in such a substrate. Unless the secondary substrate is sterile (or at least unusually clean), it will become colonized with mold and bacteria long before the fungus can fully form. This is why it is almost always grown indoors under very carefully controlled conditions.

Finally, being a tropical species, it does not grow well in cooler climates and certainly cannot withstand the sub-freezing temperatures that many places experience during the winter months. Luckily for the mushroom cultivator, there are a number of other Psilocybe species that do the job. These are the primary saprophytes or dead wood fungi, a group of psilocybin-containing fungi that are capable of growing on wood chips or bark mulch and, due to their appearance, are collectively known as “candy caps.” This group includes up to 10 species, including Psilocybe cyanescens, P. azurescens, and P. cyanofibrillosa, which are all native to the Pacific Northwest United States. There are Eastern European species of Psilocybe, such as P. Serbica and P. bohemica, as well as Psilocybe subaeruginosa and P. tasmaniana, which are native to Australia and New Zealand.

Psilocybe cyanescens is a moderately vigorous species commonly found in the Pacific Northwest, from San Francisco to Canada. Its most distinctive feature is the wavy edge of the cap, which gives the mushrooms the nickname “wavy caps.” It grows on wood chips or woody debris in lawns, in piles and along mulched paths. While the mushroom is young, it has a noticeable “web-like” partial veil, which quickly disintegrates when ripe. P. cyanescens has a relatively high psilocin content and quickly turns blue when injured.

Psilocybe azurescens is the most powerful of the known mushrooms of the genus Psilocybe. It is similar in appearance to P. cyanescens except that it lacks the wavy edge at the end of the cap and often has a pronounced "nipple" in the center of the cap, a feature known as the "umbrella cap". In nature, it typically grows on woody debris in sandy coastal soils, often under dune grasses. P. azurescens has a particularly high content of baeocystin, which may explain its supposedly unique psychedelic "signature". People who have used it generally report that it produces a deep and powerful "visionary" effect without significant physical discomfort.

Semilancelates grow in various regions of the world, including Ukraine. They prefer damp and shady areas, often growing on rotting organic matter such as fallen leaves and village litter. Distributed in western Ukraine in mountainous areas. The mushrooms are small in size, characterized by a conical cap with a convex center and a bluish tint. When ripe, the cap may become flatter and the color may change from light brown to olive brown.

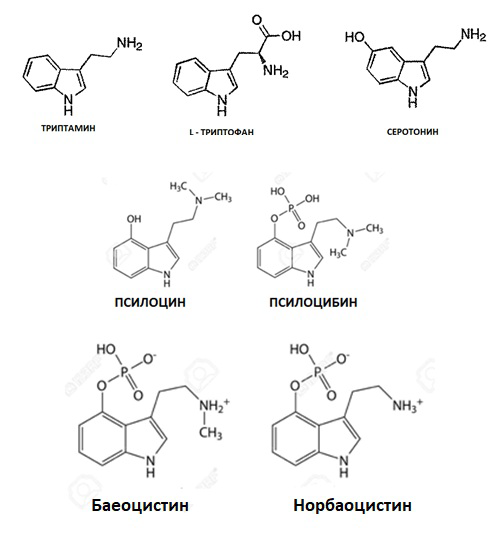

The chemical compounds found in Psilocybe mushrooms are a complex of related tryptamine compounds containing an indole ring and an amine linked by a two-carbon chain. All of these compounds are closely related to the common amino acid L-tryptophan, from which the fungus builds them, and to serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), a major neurotransmitter in mammals that helps explain their pharmacological effects in humans.

Psilocin and its phosphate ester psilocybin are the most abundant compounds found in these mushrooms, while baeocystin and norbeo(norbao-)cystine are usually present only in trace amounts, if present at all.

Psilocybin is quickly converted in the body to psilocin by removing its phosphate group, making the two compounds more or less identical in potency and psychedelic effects despite their different molecular weights. The psychoactive effects of baeocystin and norbaeocystin (in isolation) are not well understood, but there is some evidence that they modulate the psychoactive effects of psilocin and psilocybin. Their presence in varying quantities may help explain reports of subjective differences from one species of psilocybe mushroom to another.

No doubt due to numerous legal obstacles to public scientific study of these types of mushrooms, almost nothing concrete is known about why these chemicals are present in these mushrooms in the first place. Nature rarely does anything without a practical purpose, especially when the action is energetically costly, as it certainly is here. These compounds must serve as some evolutionary advantage for the survival of these fungal species in nature. Otherwise, the resources that go into their synthesis would be better spent, for example, creating more spores or larger fruiting bodies. It could be argued that these molecules ensure the survival of these types of mushrooms, since their presence encourages people to grow and propagate them due to their psychoactive effects. However, such logic does not make sense in nature, since these mushrooms managed just fine for millions of years without our help and grew on their own long before humans appeared. The chemicals they contain must have had some important purpose in their daily struggle to survive in their natural environment.

Exactly how psilocybin produces the psychedelic effects it has on the human brain is still a mystery, both due to the profound complexity of our brain functions and the legal restrictions placed on the study of psychedelic molecules. However, its main effect is thought to be primarily a result of its interaction with certain serotonin receptors. Neuroscientists refer to two general types of active molecules: agonists and antagonists.

An agonist binds to a receptor with an effect similar to the actual neurotransmitter, while an antagonist blocks the action of the neurotransmitter. Returning to the "lock and key" metaphor, the agonist is the key that fits and opens the lock, like a master key, although perhaps with more or less efficiency than the neurotransmitter itself, while the antagonist works simply like a key inserted into a lock , preventing the real key from getting into the lock itself. Psilocybin and related molecules are thought to be serotonin agonists. They bind to receptors and act on them in the same way as serotonin, but with a slightly different effect. Although the effect on each individual receptor may be minor, their overall effect on the human mind is undoubtedly deep...

Given the powerful psychedelic effects in humans, it is reasonable to wonder whether the compounds found in Psilocybe mushrooms could in any way be toxic to the health of the human brain. In fact, there is no evidence that they are poisonous at all. First of all, they are unlikely to be toxic given that they have such a long history of human use without a single attributed death. Additionally, these molecules have been repeatedly subjected to traditional toxicology tests, which have shown them to be fairly harmless. Psilocybin has an LD-50 (or 50% lethal dose) of approximately 280 mg/kg in rats and mice, which means you would need to give test animals 280 milligrams of psilocybin for every kilogram of body weight to kill half of them. Roughly speaking, what this means for humans is that an adult male with an average weight of 80 kilograms would need to eat 22 grams of pure psilocybin or something like 500 grams of dried Psilocybe cubensis mushrooms to earn a 50% chance of death! By comparison, caffeine, which is widely considered a "beneficial nervous system stimulant" for humans, has an LD-50 in rats of 192 mg/kg, making it approximately 1.5 times more "toxic" than psilocybin.

Very conditionally, one can draw some abstract boundary between the levels of psychedelic effect. Let's consider the gradation of levels of psychedelic effect.

The quantity is indicated in grams of correctly freshly dried mushroom, strain Golden Teacher species P.Cubensis.

Minimal and/or not noticeable changes in perception.

The nature and structure of thoughts changes, and it becomes possible to track them in a new way. The topic of microdosing is very actively studied in the scientific community and is practiced by many people in everyday life. Microdosing is used more for recreational and research (including medical) purposes.

Entry-level psychedelic trip.

Clearly observable changes in perception, but at the same time completely controllable. The level is suitable for communication and joint experiences, including in open spaces. Physical, mental (mental), earthly level of the trip.

The amount of mushrooms that has become the standard, the golden mean of the psychedelic experience.

Significant changes in the perception of space, time, events, and one’s role. All sorts of earthly and cosmic scenes are observed and experienced. Conscious control of these trip levels opens up incredible possibilities for programming reality (imprinting the nervous system, brain). Level of borderline state of awareness of the shape of the body and its limits. The ability to look beyond the boundaries of reality while remaining within it. Cellular, bioelectrochemical level of the trip.

Deep psychedelic experience.

The perception of reality can change so much that “not a trace will remain of the familiar world.” The experience of awareness beyond the usual form of the body, living the lives of other people and creatures, the experience of traveling in time and parallel versions of multidimensional reality, the opportunity to leave reality, experience the so-called “exit from the matrix”, realize oneself as the beginning, end and cause of all events and phenomena . Experience of dying, events after death and rebirth.

OUT SPACE.

Eating so many mushrooms is comparable to jumping with a parachute, not being sure whether there is a parachute in your backpack. This depth of trip is an attempt to experience the “absolute experience of reality.” And sometimes it still works out. However, few people have been able to describe such experiences in human language. A dangerous experience for most unprepared creatures. Nevertheless, the experience is extremely resourceful for those who are able to navigate such depths. The opportunity to realize and experience the experience of God himself, to travel through the multiverse, living entire universes and creating new ones, is an absolute loss of any ability to control anything. Merging consciousness with reality.

Currently, psilocybin-containing mushrooms are classified as substances prohibited in Ukraine. Mycelium is also prohibited from distribution. However, spore prints are allowed to be distributed because spore prints do not contain any psychoactive substances. All this information is for informational purposes only and does not call for action.

Author: Dmitry Morgan

To verify that a mushroom found in nature is psilocybin, you must have knowledge of mycology and experience collecting wild mushrooms. The reaction of turning blue when a leg is broken indicates the presence of psilocin, but is not a guarantee. Some toxic substances also turn blue when oxidized. You can determine the type or genus of psilocybin mushroom if you have access to the necessary literature with photographs of all known species.

There are two main genera of psilocybin-containing mushrooms. These are Psilocybe and Panaeolus. Paneolus and Psilocybe are genus. Cyanescens and Cubensis are the species. And already species have varieties, that is, strains. For example, Psilocybe species Cubensis, there is a strain of Golden Teacher, Tapalpa, Pink Buffalo, Thai and many others.

Only 1 type of psilocybin mushroom grows on the territory of Ukraine. Psilocybe Semilanceata. This species is common in western Ukraine in mountainous areas. The mushrooms are small in size, characterized by a conical cap with a convex center and a bluish tint. When ripe, the cap may become flatter and the color may change from light brown to olive brown.